Shelf Life with Kyle Beachy

Are you familiar with Kyle Beachy? You may remember him as the guy that wrote this article… Well first and foremost Kyle is a skateboarder, but also he’s a published author, an English and creative writing professor, a podcaster, a St. Louis native (now living in Chicago) and genuinely just a great human being. I met Kyle at Pushing Boarders in 2018 and we’ve kept in touch ever since. So when we received a few books in written by skateboarders I thought, ‘why not have Kyle review these for us? He’d be perfect for this!’ After a few discussions with Kyle and an on point illustration by James Jarvis ‘Shelf Life’ was born. In what we hope to be a continuing feature on our website Kyle will review a couple skate related books and one non-skate related book he personally recommends. As publishers of a print skateboard magazine we encourage you to rest your eyes from your screens just a little bit, put the smartphone away and check out some print media for a change. How about reading one of these books? 😉 Take it away Kyle…

Shelf Life #1 by Kyle Beachy

Top of Mason by Walker Ryan

I am a fan of Walker Ryan’s self-published first novel, though not for the usual reasons. It’s not for Ryan’s commitment to language—the writing is uneven, there’s little we see or hear that is not also explained, and about Henry, our hero, the most descriptive thing we might say is that he lacks imagination. But there’s a velocity to it all, a momentum you’ve got to admire. Once the heartbreak plot gets moving we’re on a one-way hillbomb straight into trouble. Henry gets concussed and next we know he’s smoking crack and bottoming-out in a pissy corner of a skatepark, overdressed and humiliated. But soon—like, within an hour, maybe?—he lands a high-pressure switch inward-heel at the request an old friend, Dev, and we’re back in business. Now the dream clicks into gear, and even if all feels a bit familiar, Ryan succeeds in charging this story with enough anxiety that you’re concerned even as you’re pretty certain where it’s all heading. Most importantly, you’re still reading.

I did wonder at least once whether Henry is only fortunate or, I guess, deceased—we might easily read everything that follows his very bad fall as the afterlife of a heartbroken and well intentioned, if simple, bloke. If he is alive, then he’s blessed as hell: the concussion, the crack smoking (which he enjoys very much!), the drug runners out for vengeance, and an endless cascade of shame all leave marks but fail to stop our Henry. I meanwhile couldn’t stop wondering about the festering wound on his hand, which, in another novel, a more labored and self-serious novel, might have turned into a treatise on embodiment and the frailty of the human form. But Ryan, a living breathing professional, knows skateboarding extremely well, and more than that, he trusts it. In his hands, skateboarding is only ever itself, and for that Top of Mason is a novelty, an accomplishment, and a relief.

No Beer on a Dead Planet by Jono Coote

The travelogue is the natural form for skateboard writing, or perhaps I’ve got that backwards. In any case, about two-thirds of the way through this perfectly titled, slim and spellbinding volume published by the tiny and honorable Red Fez Books, Jono Coote describes the darkening sky over the suburbs of Melbourne “holding its breath” as he hurries to wrest a skate session from “the jaws of the inevitable exhale.” Ours, Coote knows, is a world chock full of shapes and light and sounds worth noticing—like the park coping that “barks like a rabid hyena”—and he is omnivorous with his attention. Along the Eastern Coast of that distant, southern continent, Coote moves with equal parts humility and curiosity. The only times his writing gets out hand occur in the thrall of the natural wonders he’s discovered on some hike or boat ride or stretch of coastal drive. And can you blame him?

The book’s perfect title comes from the blackboard of a pub in Hobart. It is at once a fact and a terrible, arresting thought. This is where we are now—we’ve achieved a point in history that tautologies are warnings. Fires rage across 25 million acres in New South Wales. Systemic racism is as deeply embedded in Australian culture as any, every, in the world. Also: methamphetamines. Coote, meanwhile, opens his book with a land acknowledgment and makes a point to name the racism and cite aboriginal history he and his partner Alyce encounter on their travels.

He is not, let’s say, hopeful for the future. One of Coote’s alarms, however, rings flat, or fails even to muster a ring at all. This is that aging skater’s lament about parents training children toward competitive skateboarding, reducing our meaningless and baffling activity to “something you can, eventually, win at.” How ridiculous, how self-evidently stupid this concern sounds with Coote’s wonderful book resting lightly inside our hands.

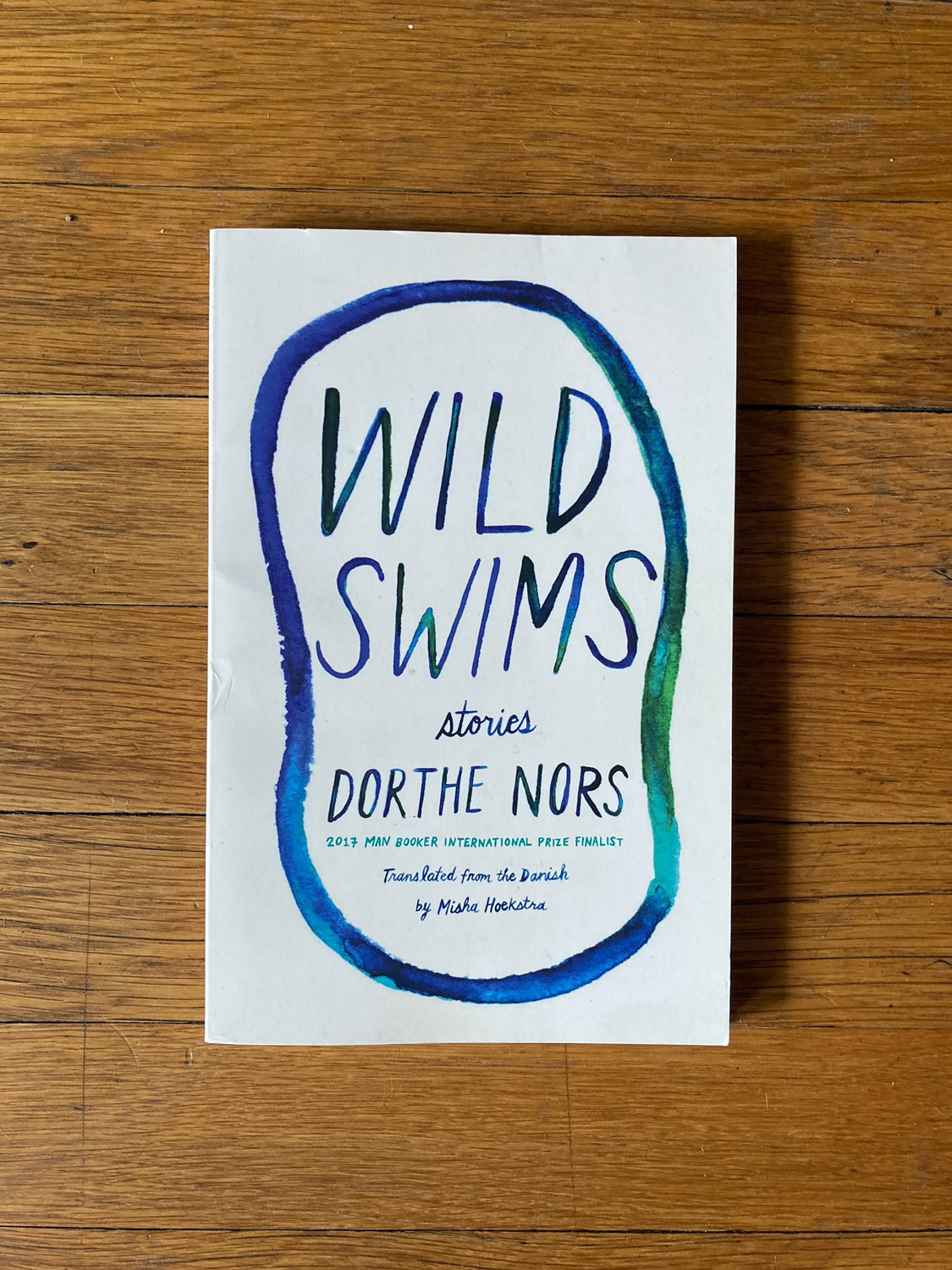

Wild Swims by Dorthe Nors

I met Dorthe Nors at an old, brick, and properly named manor house in rural Jutland. The manor is owned by the nation of Denmark, and nearby, on the estate, are the ruins of four prior structures that have shared the current manor’s name. Nors was at home in this place. I would go out walking and get lost immediately, though not unpleasantly. There was a chapel and a graveyard and a massive wall of uncut timber, swaths of forest with footpaths that wound through ravines and ran up and down wooded hillsides and then suddenly opened into great fields of heather, silent and waving in the breeze.

The tension between Jutland and cosmopolitan Copenhagen runs through all of Nors’s work—which is among the most compelling and distinctive fiction being written today—even the stories set far from Denmark. She believes in two things, at least: privacy and contradiction. In her last collection, Karate Chop, a narrator notes of a man that, “He wishes both of them well. Yet he also wants to do them harm.” That the prior does not preclude the latter is one of those persistent human mysteries that make vital the practice of literature. In Wild Swim, we see the faint glow coming from behind a tree in the yard, “but it’s probably no one,” she tells us.

The technique is a kind of existential understatement balanced with an almost skaterly love of mischief. Nobody alive withholds and apportions information as effectively as Nors. Reading her can feel like standing alone in a field as, slowly, a house is erected around you. Half of the house, the bricks, are called information. The other half, the timber, is called character. And as you feast upon Nors’s clear and polished sentences, you realize that, oops, both halves of this structure appear to be on fire, or at least smoldering, and also seem to be shrinking even as the house grows into its form. The effect of her stories is a pristine and often unnerving inevitability, a cutting to the bone, or rather several bones all at once.