Shelf Life #2 by Kyle Beachy

After his first book review column some months ago, Kyle Beachy has managed to find some time in his busy schedule to write up another instalment of Shelf Life. You see, Kyle has been quite consumed this year promoting his own book, The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches from a Skateboard Life, as well as skating, travelling, teaching and making cute Instagram videos with his dog Sonny. We’ve actually interviewed Kyle about his new book, which you can read here on the site soon, so keep your eyes peeled for that. But for now, Kyle is going to tell us about some other books he’s enjoyed; two by skateboarders, and one by an author he suspects you might be into.

Shelf Life #2

Kyle Beachy

On Vadi, Hölsgens, Berrera

José Vadi

Inter State: Essays from California (Soft Skull, 2021)

I will begin with three admissions. First, that the back cover of this collection of fierce and nimble essays about California—which state, lest anyone get distracted by the many and loud stories New York City tells of itself, is indeed both heart and spine of the American mythos—features a promotional blurb that I contributed at José’s request to help him and his publishers sell this, his debut book. Second, last August I sat down to a conversation with José over Zoom for a promotional event organized to sell my own book. Third, and most damning to any standard of objectivity you might expect from a book review, a month prior to that promotional conversation I met José on a blazing Oakland evening to skate the Rockridge curbs. We did slappies and pointed phone cameras at each other and discussed the dense history of that parking lot and other places nearby.

“Look,” said José, “that’s Rob Welsh.”

But what’s important is that my promotional blurb for Inter State is as honest as I can be about the book—the country that José and I share would indeed be a less wretched place if we had more writers like him, and his essays surely do present a loving, angry case against the persistent belief that men of power are also men of character. He writes of Californian soil and concrete, connecting “those fields that have been razed and seeded and destroyed and reirrigated and dammed and flooded and manipulated to a science so exploitative that the soil barely recognizes itself in these valleys of abundance, exportation, growth, and water,” to street skating’s Bay Area foundations in “the ubiquitous shadows of an investment group’s skyscraper.”

It is a magic act of the truest sort. And since writing my promotional blurb I have, as I threatened, gone back to read this book again. I found it even more rewarding this time, as I knew I would.

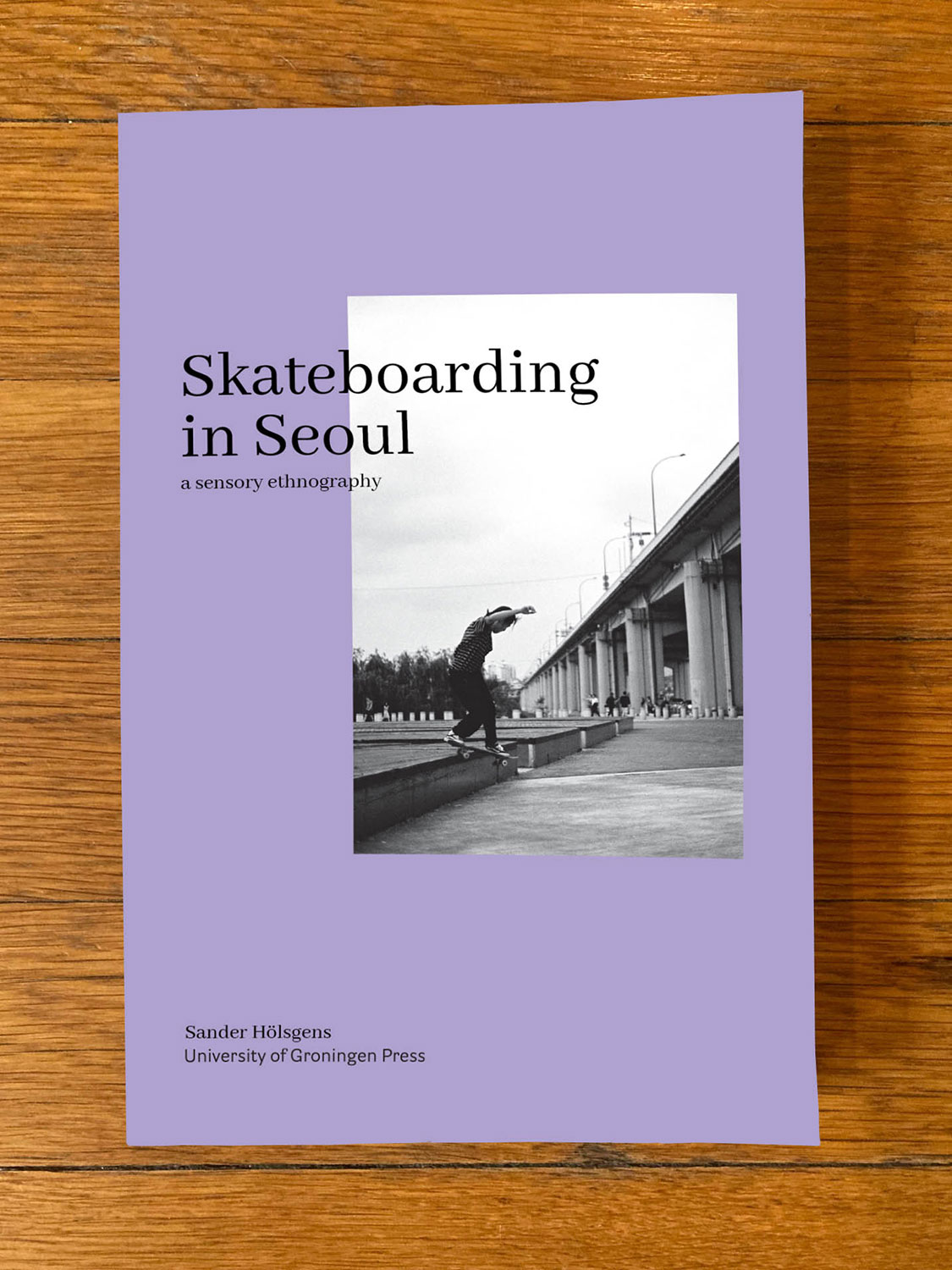

Sander Hölsgens

Skateboarding in Seoul: A Sensory Ethnography (University of Groningen, 2021)

Friends, do not blame the skateboard academics. Ignore them if you choose, and even doubt if you like the purity of their interests in your life’s primary love, this bodily practice that lives beneath thought and ripples through your skin and bones in ways that require no language, least of all such rigid and formal codes as theirs, least of all footnotes, citations, and hyphenates. Every world has its conventions. And, I wonder, have you heard how some of us speak? We are not exactly innocent the silliness of made-up terms.

In Skateboarding in Seoul, Hölsgens gives us—for free, thanks to a creative commons license—a site-specific study via methods he describes as “researching-with and making-with.” He was not only embedded among skaters in Seoul, but was in fact a skater among skaters in Seoul. Which perhaps matters to you, that Hölsgens is not “only” an academic but also a skater and filmmaker, and that indeed his book includes a quietly beautiful and meditative film, “Reverberations,” to accompany, illustrate, and enlarge upon the text. His lineage includes, among many others (the book’s bibliography runs nine pages), Iain Borden, Ocean Howell, Asa Berg, and other names familiar to anyone who follows this particular junket.

None of whom have turned quite as hard as Hölsgens has to phenomenology. From Heidegger’s notion of attunement through Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Hubert Dreyfus on theories of coping, here is an enriched account of that famous “skater’s eye,” including an argument that skateparks compromise this perceptual practice that’s so central to the skateboard activity. In Seoul, we learn, parks function as restful and semi-familial respites to the prevailing living conditions of the city. Squint a little and this should start feeling familiar. What the academy calls ethnography is just another term for the deepest, most comprehensive scene report you’ll encounter.

Jazmina Berrera

On Lighthouses (Trans. Christina Macsweeny, Two Lines, 2020)

What a delight, the book that reveals its intricacy the longer you spend time in its company. Books are not people but they are not far off, the best of them. This slim, pocketable volume from Berrera, a Mexican writer living in New York City when she wrote it, is about lighthouses, as it claims, but behind the six structures she visits is the matter of collecting as a practice, that unfinishable quest that so many of us take up in some form or other. And why? Why search out and accumulate? Skateboards, stickers, and silly shot glasses. Landmarks, ballparks, and the graves of famous rock stars.

For Berrera, it’s a matter of collapsing distance, a satisfaction that repeats as each new object comes into the collector’s grasp. Pointing at the prepositional title of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, she situates this “to” as an “archetype of a promise, the expectation of happiness that can sometimes be confused with, or perhaps is, happiness.” I love this line. Elsewhere, she wonders if it’s possible “to separate the concept of collecting from culture.” And like any good essay, its reader will find itself wondering along with it—What is the relationship between collecting and happiness? Or, if we’re feeling bold, what is the relationship between culture and happiness?

Distance, here, is not only a theme—what I love most about this book is the way it conveys the physical sensation of distance. I mean that distance is both Berrera’s subject matter and a formal technique, which manifests as an affect for the reader. There’s a coolness to the book like the light blue of its US hardcover, a blue of openness and clarity, one that reminds us that whatever else it is, distance is always an invitation, a potential for future closeness.